An interdisciplinary performance artist discusses their African indigenous knowledge-inspired work, which merges medium and community activism. Exploring the body as a contested site, the artist weaves humor with serious themes such as labor and politics. Utilizing ritual and play, they engage audiences, challenging cultural perceptions, particularly of the black male body. The artist’s new project, MORWALO, is a meditative process using bubble wrap and mosquitoes net to explore memory, vulnerability, and societal wounds. They’ve embraced solitude in creation, with the project marking a significant growth in their artistic journey.

What inspired you to become an interdisciplinary performance artist, seamlessly blending various mediums like performance installation, photography, film, and activism into your work?

It is through African indigenous knowledge that I come to understand and unpack my artistic practice. It is also through African indigenous knowledge that I locate and borrow key elements of performance especially in relation to ritual and communal performances, theatre in the round, site-specific performances and the exchange of cultural knowledge in a shared communal space. This is important as it transmits and conserves the accumulated wisdom of the family, the clan and the ethnic group by allowing my artistic practice to be morphed and reshaped, almost in a way that water takes on the shape of varying vessels. This has allowed my practice to manifest in various mediums because it is an expression of accumulated wisdom from the self, family and clan (broad community). I am informed by community, performing community and being community. I am community before I am a interdisciplinary performance artist. Wherever I land, that is my community and if something affects and seeks effect then that lands as activism because I am provoking and the community is provoking. We respond. We are all interdisciplinary community.

Your approach to the body as a contested site of labor is both thought- provoking and playful. Can you share how you navigate the serious themes of labor and politics while infusing humor and satire into your art?

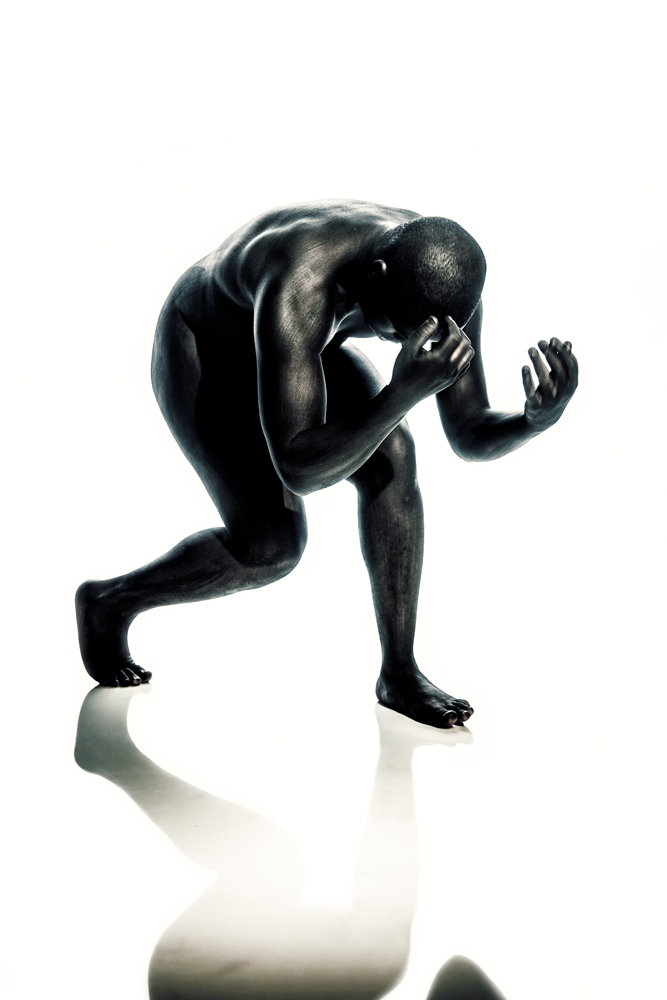

What is the colour of the brain? What is the colour of water? Their colours can only be defined by the objects carrying them. That is the first problem in my work? Is that we have reduced our souls and spirits to be defined by the shapes and colours of our bodies. I am interested in the water and the brain carried by each body and not necessary by the body. BUT it all starts in the body, it is covered and hidden in the body.

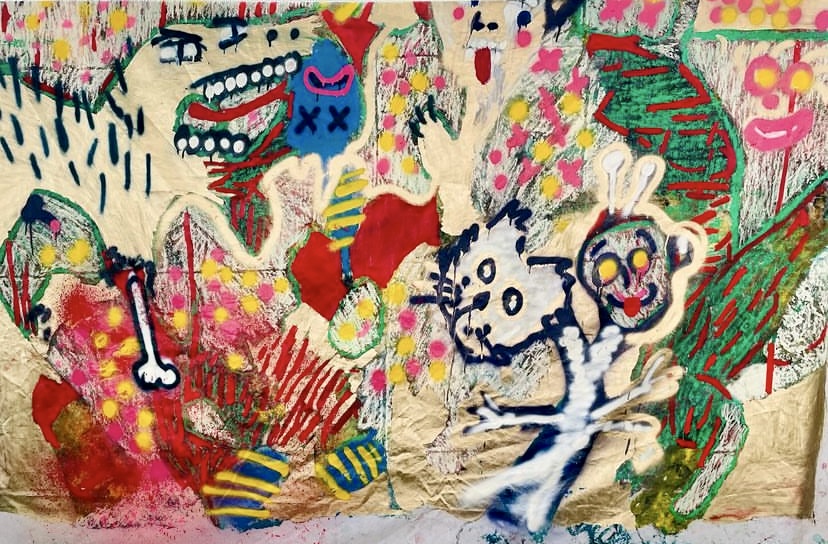

In my work, the body is a site of making meaning, ideological struggle and performative resistance. Emphasis is placed on the body; its power, vulnerability, sexuality, objectification; its memory and its capacity for violence or intimacy; the body as it exists or is represented publicly and privately, symbolically and commercially. I explore the tensions that exist between ritual and play as encompassing us to understand the deeply woven relationship people have with their corporeality as a spiritual manifestation for resistance and survival.

Furthermore, my work uses ideas and methodologies of play and performance as ways to reflect on “improvisation”, “make-believe”, and “staging” as modes of survival, and ways in which people have historically recreated cultures through embodied, reflexive, and collaborative ways. In challenging existing modes of cultural production & consumption, academic research, a central concern is to present different ways of knowing people, a culture, in order to shift away from the modes in which the most prominent discourses around culture are spaces in which peoples bodies and cultures are objectified as something alien and far from the human.

My work is about my body, the accumulation of bodies and the embodiment of the different bodies some bodies are playful while some bodies are provocative and speak with a forked tongue.

Ritualistic performance and play are central to your work, enabling affective and relational encounters. How do you believe these elements enhance the audience’s engagement with your art and its themes?

In thinking of the intersections between ritual and play, I wish to focus on the status we embody when we undergo a ritual of play. In play, one takes on a status that is not embodied every day. Just as in a ritual, one ultimately steps out of the everyday self in order to embody a seeking of harmony or a need to bring balance, for example. The phase of separation exists both in play and in ritual, and marrying the two (ritual and play) is crucial in my practice, despite the fact that a ritual is perceived to be sacred while a play is usually seen as frivolous.

Rituals are secular and sacred, comprising of three phases which are separation, transition and reintegration. According to me, it is these three phases that make a ritual to be sacred as they work towards personal and interpersonal stability. However, my practice goes further than these three phases but into the multidimensionality of ritual as something that is cyclic in nature and cannot be explained through the limitations of academic language or linear thinking. My references are located elsewhere; fundamentally, the African traditional customs and practices emphasize the close connections between the empirical world and the cosmos. Parallels can be drawn between the consequences of good and bad, given the cosmological world and the empirical world, and in consequence, judges humanity according to the virtue of their deeds. Given the complexity of rituals, I am not limiting myself to the confines of the three phases of ritual but I am looking at the possibilities they offer to escape or reconfigure everyday reality over time.

I utilize the collaboration between my body, mind and spirit to create a platform wherein the spirit of movement and expression allows viewers to critically engage with approaches to the body, particularly the black male body. Though my work deals largely with complex and thought-provoking themes, my artistry heavily invokes the spirit of play, going beyond its associated frivolity, and using it as a channel through which people can engage with each other, and the issues affecting them, in a light, accessible manner. Through play, my prayer is always that my work communicates and embodies the knowledge of the artist, acting, in turn, as an imaginative exploration of the world around me by borrowing elements of performance through the exchange of cultural knowledge and ritualistic communal practices.

Its never an easy way with my audience, others play with me and others walk away cursing me and that is still playing too. Other kids curse when they play. My relationship with audience is a frivolous one because not only do I play to celebrate but I play fighting for justice.

Your focus on the black male body and the history of representation is crucial in today’s discourse. How do you navigate the complexities of representing these subjects while addressing themes like pain, spectacle, and negation?

My creative research or practice cannot be read through a single temporality, as the crux of the work lies in the complexity of the contradictions, congruencies and differences evident in the work in relation to my and other’s relationship to the black male body and the history of representation. Even those concepts that are tenuously established, suspended between questioning and certainty, hovering between ordinary word and theoretical tool, constitute the backbone of the interdisciplinary study of culture primarily because of their potential intersubjectivity.

My work is about reclaiming my authentic voice, digging deep within me and going back to my African traditional treasures to find that which speaks to me. By navigating these emotional charged themes through play, I protect myself from trauma but turn them into themes for collective mourning especially in times of gradual global collapse as reflected by the current world we live in. The neglect of the black boy child is what prompted me to work with themes like pain, spectacle and negation. My art is made of the same material as the social exchanges, it has a special place in the collective production process. The work actually portrays not only its manufacturing and production process, its position within the set of exchanges, and the place, or function, it allocates to the beholder, but also the creative behaviour of the artist. If the artist is undergoing pain, that is a reflection of human pain, if the artist is being discriminated the attitude of the work will reflect the overall behaviour of where he is.

My work developed largely to portray black pain and black spectacle largely influenced by the neglect of the black boy child. Especially in South Africa. I am interested in shining a spotlight on the pain of the black boy child but also the talent that the black boy has only when supported and hand held. I lost my grandmother Ouma Sibeko when I was 10 years old and her final words were, “don’t forget to play”. It is her words that allow me to embrace both the beauty and the ugly. The pain and the spectacle. It is her words that influence my artistry. That is my navigation and way of protecting myself.

Your new project seems to explore a unique theme. Can you give us a sneak peek into the inspiration behind it and what audiences can expect to experience?

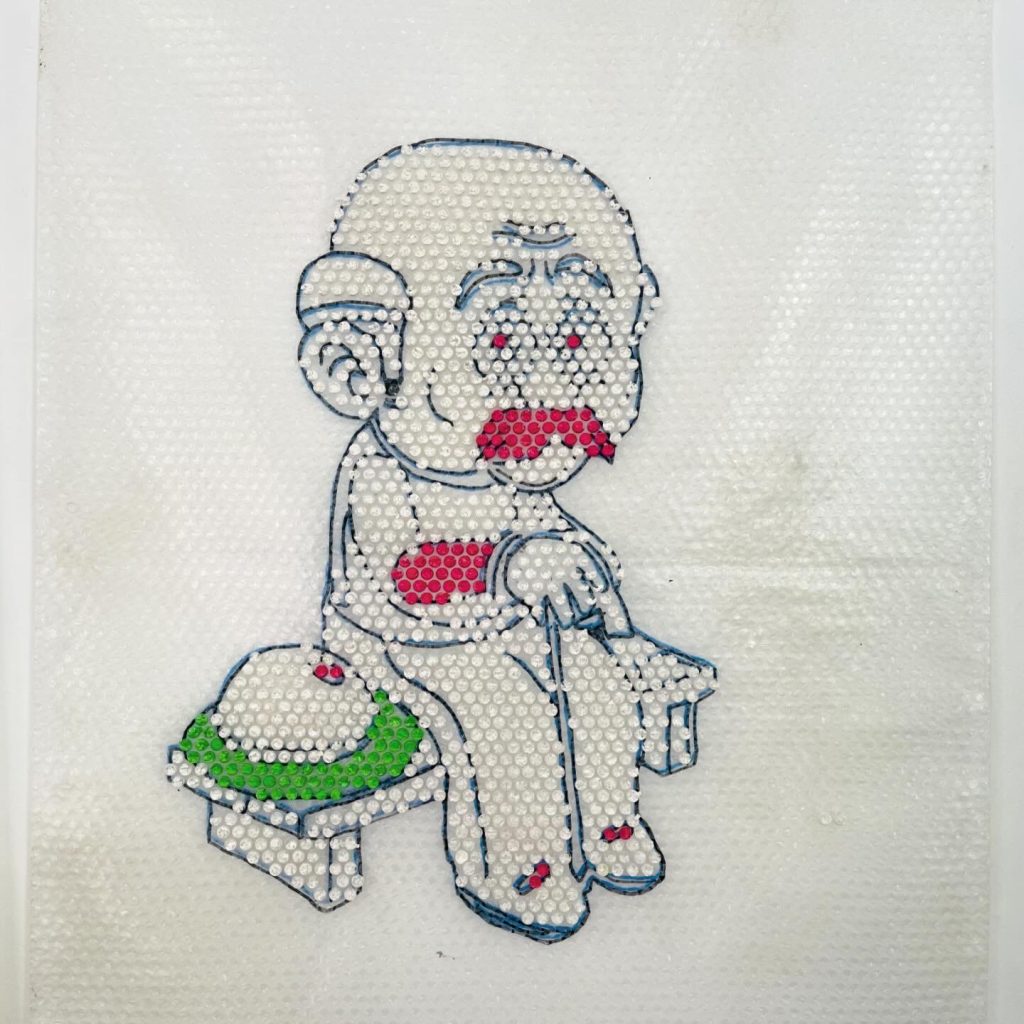

The new project is called MORWALO, which translates to baggage. I am at the baggage claim. I am here to embrace and carry my baggage. The project places the audience or viewers at the baggage claim, at the spiritual baggage claim. For the last three years I have been travelling between Africa and Europe with bubble wrap. I have been painting and injecting paint of bubble wrap for the last 3 years in residency and across various festivals from New York to Stuttgart.

This new project sees me painting and presenting the paintings for the first time. It sees me embracing a medium never once explored. But it sees me approach this medium foregrounding the materiality of the art as the narrative device. In my latest project materiality becomes the golden thread that weaves together the expression of colour both neat and occasionally wild in painting and performance. Having a firm root in the performative ways of cultural production, my latest project sees me working with bubble wrap and mosquitoes net to speak on memory and near-forgotten narratives. Through this material and my artistic background of performance now being fused with painting on bubble wrap and mosquitoes net, I am exploring narrative possibilities available to me and not ‘constraints’ created by making an object, an art object.

The interest in bubble wrap lies in its power to unlock childhood memories or its power to bring care and protect the things we deem precious. However, in this project the bubble wrap hold the paint which in turn is moulded into memory. The king and servant are both equal in the eyes of the mosquitoes. It is the mosquitoes net employed as a political narrative device that brings us to themes of irrationality, vulnerability, pain, joy and memory.

Your previous works have been known for their innovative use of mediums. Can you share any exciting techniques or mediums you’ve incorporated into this new body of work?

Well, this project is perhaps one of the most patience demanding work I have done. I am working with a sensitive material, bubble wrap and inject paint onto each bubble. So the is very meditative and therapeutic allowing one to be still and embrace silence. The technique is laborious and it has broken me to softness. I think it is exciting that I get to share this studio process that has taken over 3 years to develop is coming to live.

Not only am I painting on bubble wrap but the process has led me to painting on mosquitoes net. The technique is frottage of potholes found on the streets of District Six in Cape Town. I am looking at distraction and softness. Can a protest, a cry be soft especially in times when one has a wound that just wont heal. Potholes are a big problem in South Africa but the potholes in District Six are also a reflection a wound that was man made. The mosquitoes net is the softness and transparency that we need to understand the full spectrum of a gaping hole. District Six, a wound that will forever be visible.

Collaboration often plays a significant role in artistic endeavors. Have you collaborated with anyone on this project, and if so, how did it enhance the creative process?

We can never pop bubble wrap or paint the same way. In this project I am whole-heartedly embracing a medium for the first time so I saw it fit to dig deep and work alone as I am trying to find my font and texture of painting. So it has been a spiritually uplifting and growth to be alone in studio in Leipzig, Stuttgart and now Cape Town. As mentioned above, this has been a 3 year ongoing project and I am finally happy to show my paintings at home. If anything, this decision has shocked a lot of people who at the exhibition opening at Nel Gallery in Cape Town were surprised that I paint as they came expecting a performance but found it on video and paintings hanging all around the gallery.

I have worked with various artists on various capacities ranging from filming, editing, painting, performance in this project. The artists include, Alia Hamdans, Moe Thet Han, Tusevo Landu, Jan-Henri Booyens, Nomathamsanqa Sibeko , Luan Nel , Kamogelo Walaza Kamogelo Walaza and Red Sibeko to mention a few.

As an artist, growth and evolution are constant. How do you feel this new project represents a departure or progression from your previous work, and what discoveries have you made along the way?

Pulling my phone up off the floor by the phone charger is the closest I’ll ever come to fishing. Pulling my paintings up off my heart and body, its crucial to reel the cord in slow so as not to lose the craft. I am fishing, I am painting. I am painting, I am fishing. I have discovered I can fish and I am going to paint more.